by Simon Black

February 9, 2017

Santiago, Chile

There are lots of famous investors and hedge fund managers who are legendary stock-pickers.

Warren Buffet is a great example.

Others are hard-core quantitative analysts who build complex trading algorithms.

Ray Dalio, the billionaire founder of Bridgewater Associates, is neither.

He’s a macro investor whose fortune was built on an uncanny ability to spot big macro trends.

He predicted in 2007, for example, that the US housing bubble would burst, and warned the Bush administration that major banks were on the verge of collapse.

The government ignored him.

February 9, 2017

Santiago, Chile

There are lots of famous investors and hedge fund managers who are legendary stock-pickers.

Warren Buffet is a great example.

Others are hard-core quantitative analysts who build complex trading algorithms.

Ray Dalio, the billionaire founder of Bridgewater Associates, is neither.

He’s a macro investor whose fortune was built on an uncanny ability to spot big macro trends.

He predicted in 2007, for example, that the US housing bubble would burst, and warned the Bush administration that major banks were on the verge of collapse.

The government ignored him.

After the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers, Dalio immediately recognized that the Federal Reserve would have to print trillions of dollars to bail out the system... so he positioned his firm for big profits, buying assets like gold and foreign currencies.

Dalio was right again.

Now Dalio has a new warning for anyone who’s willing to listen.

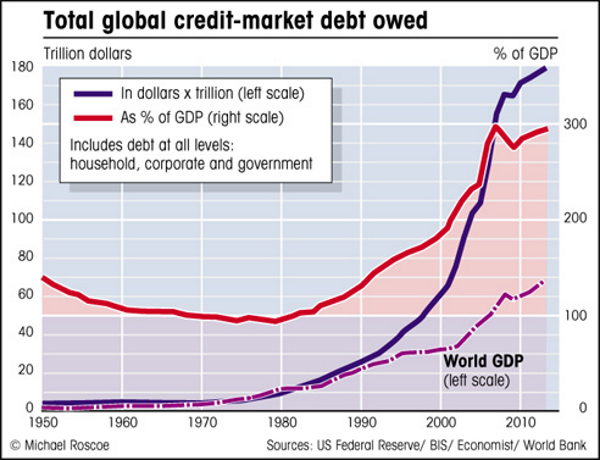

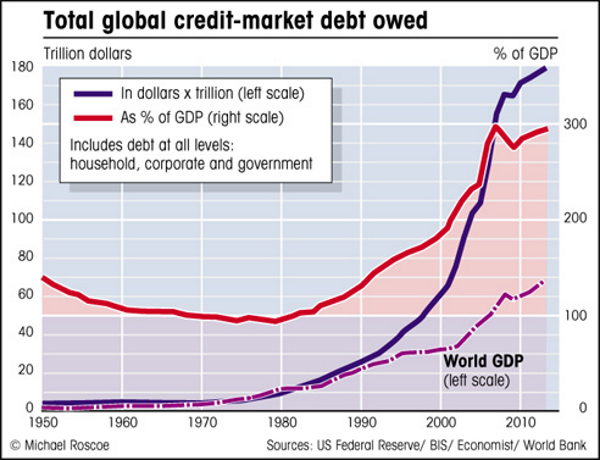

In October he admonished a room full of central bankers in New York that there was simply too much debt in the world.

At the time, total global debt was an astounding $152 trillion.

Dalio was right again.

Now Dalio has a new warning for anyone who’s willing to listen.

In October he admonished a room full of central bankers in New York that there was simply too much debt in the world.

At the time, total global debt was an astounding $152 trillion.

Total debt has now risen to $217 trillion, according to a report published last month by the Institute for International Finance.

And as Dalio points out, this has consequences.

He told central bankers back in October that “there is only so much one can squeeze out of a debt cycle, and most countries are approaching those limits.”

Governments often go into debt in order to finance big spending projects which stimulate economic growth.

But eventually the amount of growth you can generate from debt reaches a point of diminishing returns.

We can already see plenty of data to support this assertion.

And as Dalio points out, this has consequences.

He told central bankers back in October that “there is only so much one can squeeze out of a debt cycle, and most countries are approaching those limits.”

Governments often go into debt in order to finance big spending projects which stimulate economic growth.

But eventually the amount of growth you can generate from debt reaches a point of diminishing returns.

We can already see plenty of data to support this assertion.

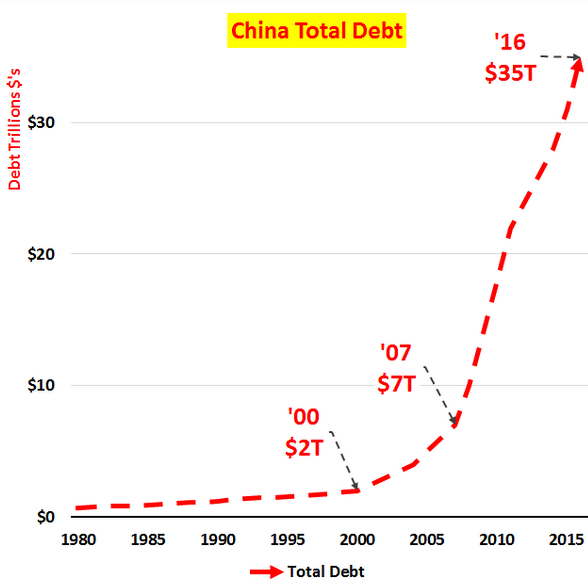

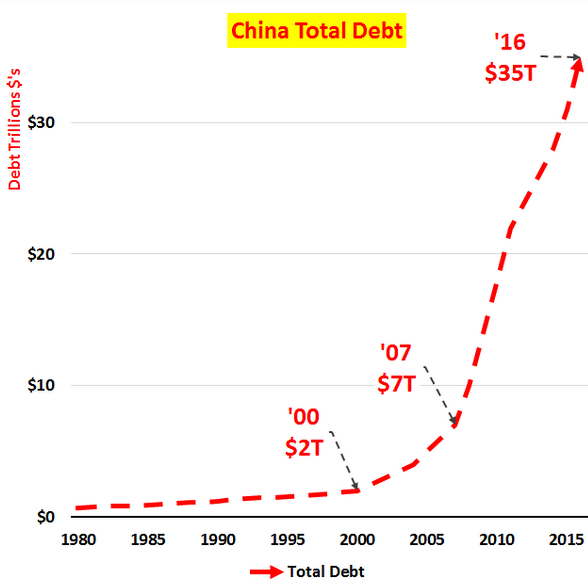

China has taken on hundreds of billions of debt over the last several years in order to maintain its economic growth.

But measures of China’s “debt efficiency” now show, according to the Wall Street Journal, that it takes “increasingly more debt to generate the same GDP growth.”

So China is rapidly reaching its limit in terms of how much economic growth it can squeeze from its debt.

Debt, i.e. government bonds, are supposed to be boring, low-risk investments.

But measures of China’s “debt efficiency” now show, according to the Wall Street Journal, that it takes “increasingly more debt to generate the same GDP growth.”

So China is rapidly reaching its limit in terms of how much economic growth it can squeeze from its debt.

Debt, i.e. government bonds, are supposed to be boring, low-risk investments.

Grandparents buy government savings bonds for their grandkids. Retirees and pension funds hold them as “risk free” assets.

But in a recent piece written for the Economist, Dalio suggests that “the bond market is risky now and will get more so. Rarely do investors encounter a market that is so clearly overvalued and so close to its clearly defined limits…”

He bleakly projects that “investment returns will be very low” and that investment risk will increase, i.e. the “reward-to-risk ratio will worsen.”

Dalio concludes his piece predicting that “savers will seek to escape financial assets and shift to gold and similar non-monetary preserves of wealth, especially as social and political tensions intensify.”

The funny thing about these big-picture, macro trend predictions, is that they seem so obvious in retrospect.

But in a recent piece written for the Economist, Dalio suggests that “the bond market is risky now and will get more so. Rarely do investors encounter a market that is so clearly overvalued and so close to its clearly defined limits…”

He bleakly projects that “investment returns will be very low” and that investment risk will increase, i.e. the “reward-to-risk ratio will worsen.”

Dalio concludes his piece predicting that “savers will seek to escape financial assets and shift to gold and similar non-monetary preserves of wealth, especially as social and political tensions intensify.”

The funny thing about these big-picture, macro trend predictions, is that they seem so obvious in retrospect.

Just look at the 2008 financial crisis.

Banks had spent years accumulating $1.3 trillion worth of no-money-down mortgages made to unemployed borrowers with terrible credit.

Eventually the entire financial system blew up.

Duh. It makes so much sense looking back.

But in 2007 almost everyone thought the boom would last forever.

Nearly every major crisis begins with a false set of beliefs, like “housing prices always go up.”

And after the collapse everyone wonders how we could have believed such nonsense.

Today’s false belief is that these unsustainable debts don’t matter.

Looking back a few years from now it will seem painfully obvious.

Banks had spent years accumulating $1.3 trillion worth of no-money-down mortgages made to unemployed borrowers with terrible credit.

Eventually the entire financial system blew up.

Duh. It makes so much sense looking back.

But in 2007 almost everyone thought the boom would last forever.

Nearly every major crisis begins with a false set of beliefs, like “housing prices always go up.”

And after the collapse everyone wonders how we could have believed such nonsense.

Today’s false belief is that these unsustainable debts don’t matter.

Looking back a few years from now it will seem painfully obvious.

$200+ trillion in global debt? $20+ trillion in US debt? Did we seriously believe this would turn out OK?

Dalio’s is a powerful warning, and he poses a logical solution: precious metals and real assets.

Maybe he’s wrong. Maybe $200+ trillion in debt really is consequence free.

Maybe the ultimate false belief of “This time is different” turns out to be true.

Maybe.

But it’s hard to imagine you’ll be worse off taking some very simple steps to reduce your exposure to such obvious risks.

Until tomorrow,

Simon Black

Founder, SovereignMan.com

PS:

Consider a membership in Sovereign Man: Confidential to learn about the most cutting edge ways to invest in real assets and reduce your exposure to these obvious risks.

Dalio’s is a powerful warning, and he poses a logical solution: precious metals and real assets.

Maybe he’s wrong. Maybe $200+ trillion in debt really is consequence free.

Maybe the ultimate false belief of “This time is different” turns out to be true.

Maybe.

But it’s hard to imagine you’ll be worse off taking some very simple steps to reduce your exposure to such obvious risks.

Until tomorrow,

Simon Black

Founder, SovereignMan.com

PS:

Consider a membership in Sovereign Man: Confidential to learn about the most cutting edge ways to invest in real assets and reduce your exposure to these obvious risks.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment